By Luis Aponte-Parés

Tourism is one of the largest industries in the world today. Its impact on the environment, national economies, technology, social mores, health, culture and an array of other areas is very large and difficult to capture. In the academic world, the study of tourism and leisure has become a major focus of several disciplines. Of these, one area that is still in need of attention is the history of tourism and its nexus with colonialism.

The United States as Imperial Republic

In my research I am exploring the relationship between tourism, colonialism and empire, in particular the U.S. as an imperial republic. Although this is not the venue to fully examine the history of the U.S. as empire, the case of Puerto Rico, one of a handful of U.S. tropical possessions, is illustrative of the way imperial metropolises “invented” their colonies and their people. In contrast to European nations, the imperial designs of which were celebrated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in the case of the British Empire, the United States has been in denial about its imperial goals, and for that matter its imperial history. The acquisition of Florida, the Louisiana Purchase and the taking of Texas and the northernmost provinces of Mexico through war provided the bases for a transcontinental nation. The final wars of expulsion—of the native inhabitants of North America from their land—were completed during the same period. To these conquests, Alaska, Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Cuba and an assortment of other Pacific Islands were added at the end of the nineteenth century.

These latter acquisitions had one thing in common: they were the lands of people whose racial and cultural identity was considered suspect in a period when the United States was defining itself as a nation. Although the establishment of the republic was an eighteenth century affair, the nineteenth century was clearly the period when the narrative “inventing” the United States was completed, using Benedict Anderson’s well-established concept of an “imagined community.” Inventing the societies and people of the newly acquired lands as “other” served to define the United States and its people as being in contrast. This “invention” was narrated in consumption venues, like magazines, travel guides and textbooks. Explaining the new lands and their people was key to maintaining the narrative of the U.S. as a country whose “manifest destiny” was to “better” the “other” less civilized societies through conquest. Notions of racial superiority and the blessings of a Christian God became defining characteristics of this Anglo-Saxon nation.

The acquisition of Puerto Rico in 1898 required an “explanation” to U.S. society. Reviewing the way other lands became part of the U.S. suggests that at each juncture, the need to “explain” the new lands and the populations already living in them was key to their inclusion/exclusion, and it placed in a cultural/racial hierarchy the ongoing narrative of U.S. society. The “imperial archives,” the historical record found in non-fiction and fiction publications of the period, suggests that to the conqueror it was clear that all populations living in newly acquired lands were considered inferior and thus needed to be either exterminated (First Peoples, a.k.a. American Indians), debased and humiliated (Mexicans, Hawaiians, Alaskans) or enslaved (people from Africa in the southern territories). Even the “white” populations that were part of these lands were considered suspect since most were from southern European stock (Spanish, Portuguese, French) and Catholic. The invention of these “other” societies was added to the overall understanding of the U.S. as a “unique” experiment in history, thus differentiating U.S. history further form the rest of the Americas, similar post-colonial societies also going through their own invention project as nations. Latin America and Anglo America became totally different twins.

Tourism and Postcards of Invention

Tourism and its attendant corollaries played an important role in inventing the Puerto Rican as “other” through representations of the Island and its inhabitants in pop culture venues like travel guides, mass consumption magazines, postcards and purported scientific magazines like National Geographic. Tropicalizing Puerto Rico was critical to the creation of a clearly inferior subject people, and to achieve this, two key elements needed to be invented: the “tropics” and the “tropical subject.” The tropics, somewhat contradictorily, were all of the following: places of disease; wonderful places to get cured; very productive land leading to a society lacking incentives for development; good for agriculture and a provider of raw materials; and great places for tourism and sex. Similarly, the tropical subject was: child-like; innocent and naive; sensuous; lazy; untrustworthy; and passive. As Frantz Fanon wrote in Black Skin, White Masks, “A white man addressing a Negro behaves exactly like an adult with a child and starts smirking, whispering, patronizing, cozening.”

Over the years, I have collected hundreds of early postcards representing Puerto Rico. Although postcards were a relatively new medium, their role was powerful in shaping the images of the colonized by different metropolises across the globe. In dialogue with my postcard collection, I like to pose questions. Who took the photo and why was the subject chosen? Who were the “models” (subjects)? Did they “volunteer”? If so, why? Who sent the postcard and why this or that particular postcard? And finally, Who received the card, and what message(s) did they get from the postcard?

Postcard “reading” is contextualized by reviewing the multitude of venues—for example, postcards, books, other publications and theater—utilized by the U.S. acting as a traditional “metropolis” while in the process of nation-/empire-building. The use of postcards, a relatively new technology, would be a harbinger of the development of a visual culture that permeated society in the twentieth century. The case of Puerto Rico was not unique. Puerto Rico, Hawaii, the Philippines and other islands across the Pacific, along with Mexico and the rest of Latin America, were part of a nascent travel industry.

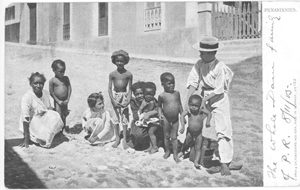

To briefly illustrate, let’s look at a postcard sent to Yonkers, New York, from Puerto Rico in 1905. Tourism in Puerto Rico was not yet developed. Those who came to the island were usually related to a commercial, governmental, military, religious or scientific group. These early visitors, especially those involved in the early tourism industry, were key to developing images of Puerto Rico for the general U.S. population.

What does this postcard tell us about early twentieth century Puerto Rico and those whose “gaze” gave the “others” an understanding of us? Whose gaze should I interrogate? The gaze of the young Puerto Rican(s) whose identity is “captured” forever in a postcard, or the gaze of the photographer, who perhaps was commissioned by commercial or “scientific” sponsors?

What does this postcard tell us about early twentieth century Puerto Rico and those whose “gaze” gave the “others” an understanding of us? Whose gaze should I interrogate? The gaze of the young Puerto Rican(s) whose identity is “captured” forever in a postcard, or the gaze of the photographer, who perhaps was commissioned by commercial or “scientific” sponsors?

The photo was taken in Old San Juan. My reading explores early stages of the “imperial gaze” during the first decade of U.S. colonial rule in Puerto Rico. During this period, a very large number of publications were produced. Some were government publications dealing with information relevant to the imperial enterprise, while others, like the postcard, were part of an array of venues serving many purposes and audiences. Among these were a large number of images published in books, magazines and postcards sent to common folks in the U.S.

This particular photo uses common people as subjects, which served many purposes, one of which was to depict Puerto Ricans as non-whites. This racialization of Puerto Ricans was essential to the construction of a colonial people deemed inferior to the colonizer. The photo may have been taken at the corner of Cristo and Luna streets, right across from the cathedral in Old San Juan. Thus the “stage” for the photo was Spanish colonial architecture. The use of this architecture as background will become one of the three foundations for Puerto Rican tourism throughout most of the twentieth century: celebration of a dead empire (Spain), the tropical characteristics of the island and Puerto Rican culture. The last two, lo tropical and the national Puerto Rican culture, were two sides of the same coin.

In the photo we can see a group of children of varying ages. It is not clear if two of the figures are adults, or just older children. All the children are black except for one. I am not sure if the “white” girl is local or the daughter of a visitor, perhaps a traveler from the United States. The younger children are naked, while the older ones are clothed. Except for the “white” girl, all the children are barefoot, and all are definitely posing for the photographer. Two of the young children are looking at the older figure dressed in white wearing a Panama hat and holding a young child by his arms. Of the two looking at her, the “white” girl is clearly looking at the older girl, while the other child seems to be gazing past the figures.

Perhaps the handwritten message on the back of the postcard says it all: “The whole Darn family of P.R. 8/11/05.” Was the sender using the euphemistic phrase for dammed?

Porto Ricans and African-Americans

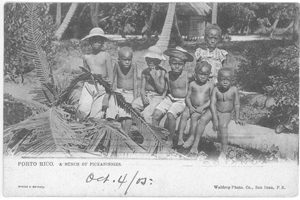

Another card entitled “Porto Rico: A Bunch of Pickaninnies” was sent to Yonkers, New York, in October 1905. The use of the “pickaninny” label, not common in the island, suggests that to some folks in the U.S., Puerto Ricans were similar to southern blacks. In fact, another card sent from New Orleans to Ohio in 1940, “Eight Little Pickaninnies Kneeling in a Row,” is a portrait of eight young men kneeling in front of a fallen palm tree. The similarities between both cards are puzzling, and the composition of the photos is almost identical. Labeling the kids pickaninnies and using a “tropical” landscape suggests either the same photographer or at least the same distribution company. The Porto Rico card was mailed in 1905 and was licensed and published by Waldrop Photo Co. in San Juan. The card, however, was printed in Germany and the photo seems to be owned by Raphael Tuck & Sons, “Art Publishers to their Majesties the King and Queen.” The New Orleans card was published by the Detroit Publishing Co. Of the three companies, Raphael Tuck & Sons and Detroit were unique in the industry for combining the printing, publishing and distribution of their wares.

Another card entitled “Porto Rico: A Bunch of Pickaninnies” was sent to Yonkers, New York, in October 1905. The use of the “pickaninny” label, not common in the island, suggests that to some folks in the U.S., Puerto Ricans were similar to southern blacks. In fact, another card sent from New Orleans to Ohio in 1940, “Eight Little Pickaninnies Kneeling in a Row,” is a portrait of eight young men kneeling in front of a fallen palm tree. The similarities between both cards are puzzling, and the composition of the photos is almost identical. Labeling the kids pickaninnies and using a “tropical” landscape suggests either the same photographer or at least the same distribution company. The Porto Rico card was mailed in 1905 and was licensed and published by Waldrop Photo Co. in San Juan. The card, however, was printed in Germany and the photo seems to be owned by Raphael Tuck & Sons, “Art Publishers to their Majesties the King and Queen.” The New Orleans card was published by the Detroit Publishing Co. Of the three companies, Raphael Tuck & Sons and Detroit were unique in the industry for combining the printing, publishing and distribution of their wares.

Using pickaninny as a descriptor for U.S. African Americans was quite common, but in the case of Puerto Rico, its use was very limited and perhaps of lesser circulation. Other similar cards, “On the Shore, Porto Rico” (1911), “They Have No Stocking to Hang, Puerto Rico” (undated) and “A Dinner Party, Puerto Rico” (undated) were faithful to the overall theme of “tropical” Puerto Ricans. Some travel guides of the period made an effort to point to the “natural” lifestyle” of Puerto Ricans during the period. The postcards could be understood as being “tongue and cheek” and quite innocent, however, they follow a common pattern most metropolises utilized in their portrayal of their subjects. Reviewing the Puerto Rican cards, it is uncanny that these photographers could “find” so many black kids, “pickaninnies” if you will, in a population that was only 38 percent “colored” (of which 83.6 percent were mulattoes) according to the U.S. Census of Porto Rico (1899).

Although not represented as “primitive” as were the Filipinos, and not exhibited in early twentieth century fairs in the U.S., the association of Puerto Ricans with the “natural” world was an attempt to connect both societies to another key theme of the U.S. Empire: the civilized and the uncivilized. Assuming that the societies that were conquered “needed” to be “civilized,” their portrayal as “uncivilized” and worthy of exhibition in the popular museums of “natural history,” so important in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, was necessary.

I would like to complete this short sketch of Puerto Rican postcards with another card, “Waiting for Uncle Sam,” published in 1900. A stereographic postcard, the photo is emblematic of the overall attempt to explain Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans to U.S. society. What could be clearer than the statement printed on the back of this card?

I would like to complete this short sketch of Puerto Rican postcards with another card, “Waiting for Uncle Sam,” published in 1900. A stereographic postcard, the photo is emblematic of the overall attempt to explain Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans to U.S. society. What could be clearer than the statement printed on the back of this card?

…and on the Porto Rican soil, where all tropical verdure thrives with great luxuriance under the sun’s warm rays, the colored children multiply and flourish without much attention or care, and are seen swarming about in all their native simplicity and innocence. Whether scrambling up the trunk of the cocoanut palm for a drink of the liquid from the nut, or playing on the beach where they watch Uncle Sam’s stately ships come to anchor, thronging about the city gates, or playing around the rude cabin doorway, they live the same free, Topsy-like life. But under the new regime, among these little natives, are we to look for the future citizens and statesmen of the island, and one of the first duties of the United States will be to establish some sort of system of compulsory education that will raise the people from the present state of woeful ignorance and provide better things for the coming generations.

Luis Aponte-Pares is associate professor of community planning at the College of Public and Community Service and director of Latino Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston. He is in the process of completing a book, Inventing Puerto Rico.