Unleashing the creative energy of ordinary people wherever we work in the world. Photos by Marie Kennedy.

INTRODUCTION

Transformative community planning is a way of working with communities across divisions. It is not based on the superficial pasting together of short-lived, issue specific coalitions, but on transforming relations between groups. In this sense, it is participatory planning which empowers the community to act in its own interests.

If we believe in participatory democracy, it is not enough to work in disadvantaged communities, it is important how we work in communities. In order to create positive social change in the face of pretty big challenges, we need to unleash the creative energies of ordinary people.

In this first part of a two-part article, I will briefly outline a definition of community development that makes sense to me, takes a quick look at the historical roots of today’s community-oriented planning, contrasts transformative planning with advocacy planning, and gives a thumbnail sketch of lessons I’ve learned through practice and engagement. The second part will look more closely at a particular case that combined professional education and community development.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Genuine community development combines material development with the development of people, increasing a community’s capacity for taking control of its own development—building critical thinking and planning abilities within the community so that development projects and planning processes can be replicated by community members in the future. A good planning project should leave a community not just with more immediate “products”—e.g. more housing—but also with an increased capacity to meet future needs. In other words, a quality and sustainable product depends on a quality and sustainable process.

Unfortunately, public policy and planning practices often do not reflect this understanding of community development. Perhaps that’s why we have so little of it. Too often, success is measured solely by the numbers—the number of houses built, clients served, jobs created, etc. Although these are important outcomes, they are insufficient for community development. And, if we measure success by the numbers alone, no matter how laudable our long-range goals, we’re going to frame our planning practice and lend our support to policies and strategies that we think are going to be successful in terms of the numbers. If we don’t include less measurable goals (or at least currently less measured goals) in our criteria for success—goals that have to do with empowerment—we’re likely to meet our goals while our communities remain underdeveloped.

On the other hand, if community development as I have defined it is our goal, in addition to looking at concrete “products”, we will be interested in evaluating how successful a planning process has been in “lifting all the voices”—in bringing previously marginalized voices into the discussion. In the planning process, how many people moved from being objects of planning to subjects of planning? How successful are we as planners in framing a process that is comfortable and encourages the participation of people who are not used to speaking in public, not facile at articulating their concerns and visions? How culturally sensitive are we to different forms of expression and self-organization? Are we able to successfully confront dynamics of racism, classism, sexism, and other exclusionary patterns of behavior that block full participation by various groups? What practical accommodations do we make to reduce the barriers to participation for groups that have been left out? Overall, how successful are we at nurturing well-informed, genuinely democratic politics and discourse, dialogue about options and about the “values” and “interests by which those options can be evaluated.

Success measured in this way requires a transformative approach to community planning.

It’s an approach that has evolved from the advocacy planning that was connected to the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

ADVOCACY PLANNING

In those years, advocacy planning began to successfully challenge the notion of planning as a “neutral science”, as apolitical. It represents an approach to planning that has been institutionalized in some limited spaces—it is a recognized paradigm taught in planning schools and it’s the approach of many community-based organizations.

Advocacy planning can also take credit for institutionalizing community participation in planning, particularly in the public sphere. Of course, this is a two-edged sword: On the one hand, mandated forums for participation can offer a foothold for struggle. On the other hand, participation today is frequently structured into a win-win framework—if we just hear from all the stakeholders, we can figure out what’s best for all. By ignoring power disparities, participation becomes a smokescreen behind which real decisions are made by those who have always made the decisions.

The terrain of struggle has changed greatly since the heyday of advocacy planning. Compared to the 1960s and 1970s, redevelopment (like everything else) is much more privatized. This means that—at least compared to things like urban renewal plans— redevelopment is much more piecemeal and the government role is secondary— supporting private developers rather than playing the organizing and coordinating role. The targets of advocacy planning are not as obvious. Development struggles are dispersed and there are fewer opportunities for broad discussions on development goals and strategies and less political pressure points.

While advocacy planning is an important thread of today’s transformative community planning, there were significant shortfalls in the vision. Debates among progressive planners today about what our practices should be are a reflection of these shortfalls.

Unconnected to social movements and mostly practiced in the CBO world, advocacy planning today is often reduced to a technocratic practice that differs from traditional planning practices only in terms of who the client is. Dependent on funding sources which usually count success by the number of products produced, the practice of advocacy planning is primarily representative, rather than participatory.

A lot of progressive planning is stuck at this place. You can be progressive in many ways— hold progressive goals—and still fall into the trap of “thinking you know better” than the folks who are experiencing the problems being addressed, and that it’ll just be faster and more effective if you do it for people rather than with them.

TRANSFORMATIVE COMMUNITY PLANNING COMPARED TO ADVOCACY PLANNING

Today, there is a spectrum of progressive planning practice—from what I am going to call an advocacy approach on one end to a transformative approach on the other end. While none of us probably works at either extreme end of this spectrum, in order to highlight differences, I will characterize the extremes.

Although advocacy planners are concerned with economic justice, with redistributing wealth, they don’t seek, in the main part, to support organizing focused on the redistribution of power and don’t aim to cede control over planning decisions to oppressed people. The model assumes that the repository of knowledge is in the planners. It’s “we’ll figure out what’s best to do and do it for you,” not, “we’ll help you do it.” On the other hand, transformative planners understand that successful redistribution of resources generally follows the redistribution of control of those resources.

Furthermore, although advocacy planners frequently have a critical analysis of the structural nature of social and urban problems, they will support organizing that focuses on issues that accept people’s existing ideology rather than trying to take up hard (and potentially divisive) questions such as racism. In part this is because this kind of issue translates more readily into products that are recognizable as legitimate results of a planning process and they concentrate on products over process and efficiency in reaching product-oriented goals over mobilization and empowerment.

Both advocacy and transformative planners would acknowledge that there is a political nature to all we do, that all of our work has implications for the distribution of power in society and that there is no such thing as a value-free social science. However, while the advocacy approach reserves this awareness to the planner, transformative planning requires the raising of political consciousness as a necessary corollary to any successful community development process.

THE TRANSFORMATIVE PLANNER

A successful transformative planner must actively listen and respect what people know, help people acknowledge what they already know, and help them back up this “common sense” and put it in a form that communicates convincingly to others. At the same time, it means challenging people on exclusionary thinking; having enough respect for people to challenge them. In working in a racially divided city such as Los Angeles or Boston, this means not basing our work on the superficial pasting together of short-lived, issue-specific coalitions, but rather focusing our work on transforming relations between groups.

Successful transformative community planning also means planners who are willing to acknowledge that into each planning situation we bring with us our own attitudes and biases—biases that flow from our own class background and location, our own gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and so forth. And, along with acknowledging the baggage we bring with us, we need to recognize that our preferences for certain planning and development outcomes are typically based, at least in part, on these biases and are not always about being “right”—our preferences are just that, they’re our preferences.

Successful transformative community planning means wielding our planning tools in a way that puts real control in the hands of people most affected—that frames real alternatives and elaborates the tradeoffs in making one choice or another. It does not mean making everybody a professional planner—a possessor of the particular set of skills that planners have developed through professional education and practice. It does mean using our skills so that people can make informed decisions for themselves. It means including the consequences of different decisions in terms of overarching community values in the trade-offs.

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE AND ENGAGEMENT

Many community development professionals are working in a transformative way and by sharing our experiences, we can help each other to be more effective in lifting all voices. I want to briefly share with you some of what I have learned from doing this work for over forty years.

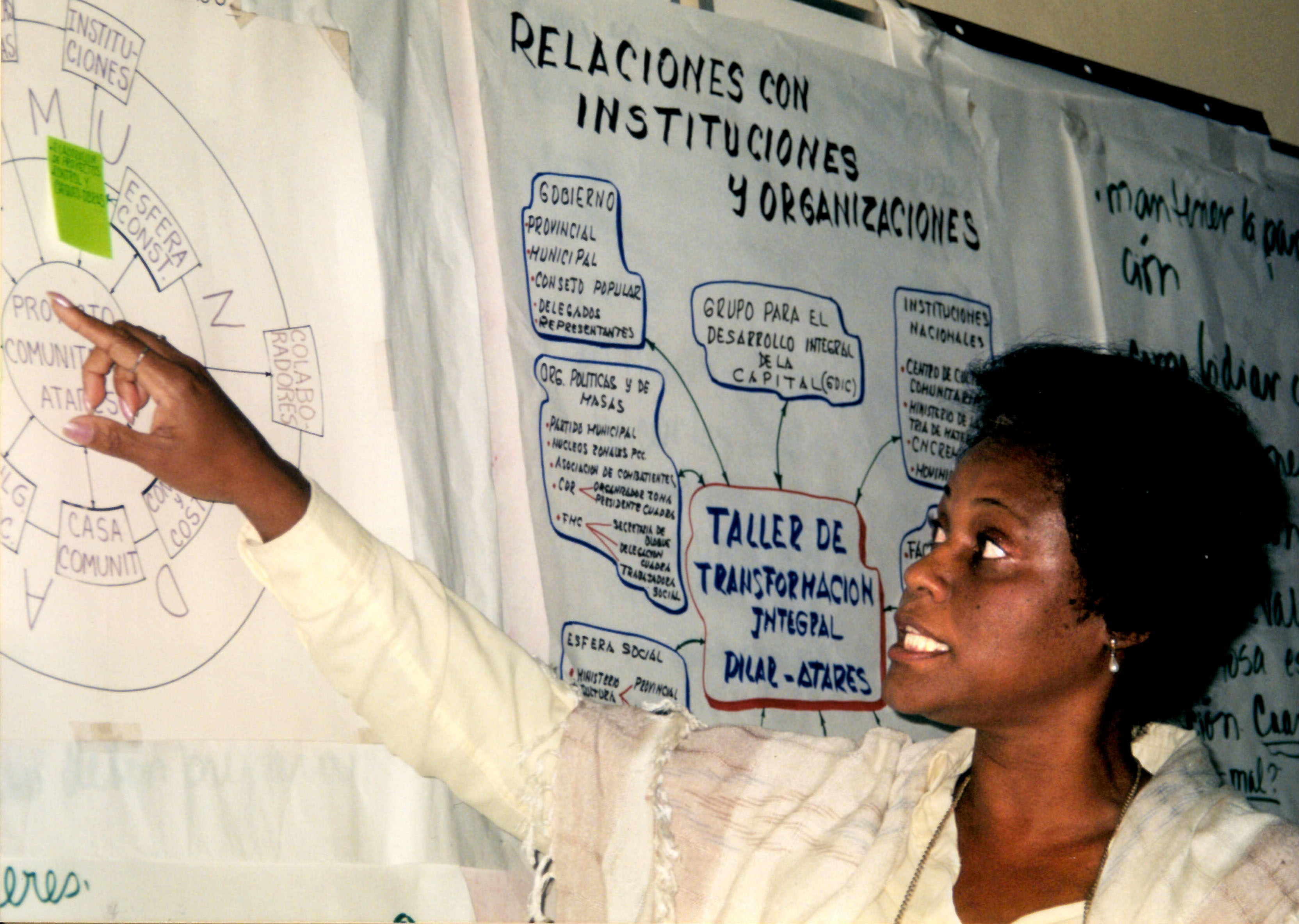

One good reason for taking the transformative approach is that even in defining what the problem is, the official experts only have part of the answer, and sometimes they don’t have a clue. In Havana, Cuba, when Mel King, Miren Uriarte and I were doing a mini-course at the university, researchers there assured us that there was no problem of drugs or domestic violence in Cuba, but when we visited Regla Barbon, the director of the Atares community workshop in Havana, she immediately identified these as two of the biggest issues in Atares neighborhood and told us of the creative ways in which they were addressing these problems. Closer to home, adult leaders in a Cambridge, Massachusetts neighborhood invited me to do a project with neighborhood youth, and confidently stated that the biggest problem was lack of jobs for teenagers. But when my students and I met with the young people, they were very clear that the biggest problem was a lack of appropriate role models.

At the same time, we need to understand how our own expertise and know-how can be helpful. In a workshop I ran in Indonesia, a big argument ensued between a social worker and an indigenous leader. The social worker, who was working for agribusiness interests on the island of Papua, complained that the natives were lazy and did not want to improve their lives. The indigenous leader angrily retorted that of course they wanted better lives, but that the 60-hour work week and bulldozed landscape being brought by palm oil plantations was destroying the things they valued most: their natural environment and time to create art and music and socialize with others. I was able to bring to the table the fact that indigenous peoples confront this kind of issue all over the world, and that we have learned from centuries of disastrous development plans that identity and culture are often the most precious things a community has.

Unleashing those creative energies means recognizing that the people best equipped to come up with solutions are often the people who experience the problems. Some people said we were nuts when, in partnership with the Women’s Institute for Housing and Economic Development, we brought a group of recently homeless women into the College of Public and Community Service at the University of Massachusetts Boston as students and had them lead a participatory research project on the issues of women and homelessness. By the end of the process, these women went to the state house to present a set of recommendations to the legislature and social service agencies based on the first large-scale survey of homeless women in Massachusetts. They really made a difference—for example, their recommendations led to changes in shelter regulations and policies for assigning housing and their success gave hope and a renewed sense of self-respect to currently homeless women.

We must also be aware, however, that plenty of ordinary people have attitudes that cut against democracy and equality and it is common for people to try to defend their little scrap of privilege against people who have less. We also have to be guided by our own values. The mostly white members of a neighborhood association adjacent to a large public housing development asked my students and I to do a project addressing the frictions that were coming up with all the new immigrants moving into the development from Haiti, Central America and Vietnam. So we met with the neighborhood association and with an immigrant-based social service agency. Pretty soon we realized that the all-white neighborhood association was not willing to let the immigrants to have a voice in the solutions. We made our choice, and from then on we just worked with the immigrant-based organization.

In fact, we often have to make special efforts to hear the voices of those who have less power and prestige in a situation. When Melvyn Colon, Kathryn Kasch, Andrea Nagel and I did a community needs assessment on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua, we realized very early on that if we just held community-wide meetings, only the men would speak. So we held separate meetings with women and with young people, and discovered they had their own ideas about what was needed.

CONCLUSION

Advocacy planning has been a critical step in the movement for planners to more directly engage with marginalized populations and provide supports to community needs. But to date much of that ‘planning’ has remained technocratic. To be transformative, a centering of community knowledge within planning is needed. This requires a reworking of how planning is done as well as how it is taught. Part two of this two-part article will explore the intersections of professional education and the potential for learning by practice as pedagogy.

Marie Kennedy is Professor Emerita of Community Planning from the University of Massachusetts Boston, former Visiting Professor in Urban Planning at the University of California Los Angeles, President of the Board of Venice Community Housing and a Contributing Editor of Progressive City. This article is an expanded version of a previous article in Progressive Planning Magazine and a talk that was given to the Mel King Institute.