By Kian Goh

“The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from that of what kind of social ties, relationships to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire.”

—David Harvey, “The Right to the City”

“. . . Queer space finds in the closet or the dark alley places where it can construct an artificial architecture of the self.”

—Aaron Betsky, Queer Space

“Our visions begin with our desires.”

—Audre Lorde

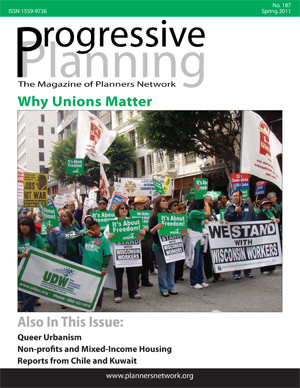

In early 2008, a group of parents and children, parks advocates and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) youth rallied together to protest the proposal for a large-scale retail and entertainment development at Pier 40, on Manhattan’s Hudson River Park. The LGBT youth, led by community organizing group FIERCE, had been working since 2000 to keep the park and piers safe and accessible. Carrying signs that read “Save the Village” and “LGBT Youth and Little Leaguers UNITE!,” queer youth and neighborhood advocates and residents formed an unlikely alliance of community opposition to large-scale privatized development.

For FIERCE, it was a particular triumph, a milestone to organizing work that had engaged and dealt with several years of tension between established West Village residents and the LGBT youth who call the piers home. From organizing in response to harassment and arrests of youth, to campaigning for later park curfew hours, to insisting on the right of queer youth to inhabit Village streets, FIERCE and their constituents fought for both a voice at the decision-making table and the right to public space.

Memorialized in the documentary Paris Is Burning, the piers at the end of Christopher Street have long been an epicenter of queer congregation. Like the bodies that inhabit them, the piers epitomize a wary comfort on the edge and, like so many edges, especially water edges, a place of possibilities. The crumbling infrastructure, left to rot after the city’s shipping heyday, offered a perfect in-between space for those looking simultaneously for escape and belonging. The piers became not only popular cruising grounds, but important centers of community, where a boy or girl getting off a bus after fleeing from far-away oppression could count on finding support and an extended family.

In recent years the piers and adjacent Hudson River Park have reflected the continuing demographic and economic changes in the West Village. Piers and park are now smartly landscaped with popular jogging and biking paths, nearby residential towers are home to some of the priciest square footage in the world and the Stonewall Inn, a few blocks down Christopher Street, is now a gay tourist destination, a mere symbol of an uprising. Many streets in the Village barely hold on to their bohemian, countercultural history, and the signs that remain are as much due to nostalgia as any kind of radical agenda. But still youth come to the piers, motivated by accounts they’ve read, watched, heard about or even something more intangible—a shared history, a cultural memory of those places of possibility.

In his book Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire, historian Aaron Betsky explores the making of queer space. He describes a space “not built, only implied, and usually invisible . . . useless, amoral and sensual space that lives only in and for experience.” Betsky’s queers, almost exclusively gay white men, through opportunism, innovation and desperation, “queered” spaces using actions, signs and symbols, particularly interstitial spaces of the city, areas of informal gathering not often in view—discos and clubs, bathhouses, bars or sections of parks at night. Queers invented, with limited resources, ephemeral spaces of display and experience within the city, new spatial and cultural permeabilities.

Early queer spaces were necessarily interior, where darkness and seclusion offered possibilities for remaking both the spaces between and the bodies themselves. Stonewall and the Castro proved decisive breakout moments—not the invention of queer spaces but the spilling out of queerness into public streets.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, queers increasingly occupied and queered public space and public imaginations. Gay pride parades grew and multiplied, slowly making the transition from protest to celebration. Groups like ACT UP stormed streets and institutions at the height of the AIDS epidemic, making demands for not just public visibility, but acknowledgement of gay bodies and gay acts in a time of crisis.

And gays enthusiastically went about the creation of distinctly gay neighborhoods in large cities across the country. From the West Village to Dupont Circle and the Castro, gays proved incredibly adept at revitalizing urban spaces. Emblazoning the exteriors in ways that reflected past splendorous interiors, such gay facades indicated when neighborhoods were safe for further exploration by less brave and foolhardy groups, often with the effect of stimulating gentrification.

Recent mainstream gay activism has steered far from its spatial repercussions. Both the gay marriage and gays-in-the-military movements constitute a desire for stamps of approval. From interiority to parades and protests to, now, efforts to get to do just like everyone else, it can be argued that, historically, the mainstream gay agenda was largely an assimilative one. It is then no surprise that public queer spaces remain ephemeral—signs and symbols remain, but the critical agenda, the instrumentality of queerness, disappears, covered and recovered by years of cultural and physical renovations.

Present-day Hudson River Park, with luxury condo towers designed by Richard Meier.

Young people on Christopher Street Piers, with Pier 40 in the background.

Photos by Kian Goh

Re-Queering

With gay neighborhoods established, tightly and seamlessly woven into the urban fabric, and pride parades not just celebratory but wholly commodified, is there still the possibility of a queer urbanism? Do queer actions still have the ability to reformat urban space?

Clearly, the demarcation of queer public space has not ceased. Even while pride parades lose their ability to shock, drowned out in thumping club music and rainbow ad banners, a number of other queer marches have sprouted in place. The increasing prominence of dyke marches across the country and the Trans Day of Action march in New York City attest to a renewed queer claim on public space.

The recent queering of ethnic pride parades as well show a fascinating confluence of often complex issues of identity, visibility and representation. In Manhattan’s Chinatown, local organizers led by Q-Wave, a queer Asian women and transgender group, have successfully petitioned for and organized an LGBT contingent in the annual Lunar New Year Parade for two years running. Similar efforts are ongoing to ensure LGBT inclusion in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade and India Independence Day Parade in the city.

Beyond parades and marches, we can also observe what could be called a conscious re-queering of spaces. FIERCE’s work on the piers is a primary example. Not content simply to ensure that successive waves of queer youth retain access to spaces of community and safety, FIERCE has held numerous organized events on the piers, including film nights and mini-balls, revisiting the days of “voguing” balls.

This kind of re-queering goes on every day, but is particularly evident in the hours after the annual gay pride parade, when thousands of young LGBT people of color flood the Hudson River Park. Kept from the piers by police barricades, young queers enact a parade of sorts along the promenade. Police control is particularly evident at these times, a reality that itself has spawned a community-based counter-movement, a cop watch project run by various local community groups tasked with keeping a record of, and hence a tether on, police harassment.

Activists led by Q-Wave organized the first LGBT contingent in the annual Lunar New Year Parade in Manhattan’s Chinatown in 2010.

Organizers from the Audre Lorde Project’s Safe Neighborhoods campaign hold a rally in Union Square.

LGBT young people led by FIERCE protest plans for privatized development at Pier 40.

Radical Queer Urbanism

Even in the age of post-queer liberation, the work of radical LGBT activists constitutes a new in-between queer space, between the increasing invisibility of mainstream gays and lesbians of television and movies, of townhouses and magazines, and the violence and discrimination that still confounds LGBT people in many parts of this country.

Distinct from previous struggles, these activists work in a space that is still relatively new for LGBT movements, carving out new spaces not only of visibility, but of safety, resilience and in public urban space, oftentimes far from established gay centers. In New York City, in addition to FIERCE, groups like Queers for Economic Justice (QEJ), the Audre Lorde Project (ALP) and Make the Road New York work to address the most critical lapses of urban services and safety.

QEJ’s Shelter Project organizers work in the city’s homeless shelters, reaching out to homeless LGBT people, offering support and community, and making connections to additional social services. QEJ’s work not only permeates the interior space of the shelter, but creates tangible connections to wider networks in the city. This work brings to light the issue of homelessness, a particularly fraught queer space all too prevalent among urban LGBT youth.

The Audre Lorde Project’s Safe Neighborhoods campaign is creating a network of safe spaces in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, without police intervention. In a country where one in every one hundred people is in the criminal justice system, ALP organizers are aware that the increased criminalization of young people of color helps no one. By establishing visible safe spaces among local businesses and gathering areas, and conducting trainings on homophobia, transphobia and ways to prevent violence without relying on law enforcement, the initiative attempts to create a new model of community accountability for safety and welfare in urban neighborhoods.

Make the Road New York’s GLOBE initiative, working largely with immigrant communities in Bushwick, Brooklyn, engages neighborhood schools as partners in creating supportive environments for LGBT youth. Sited at the intersection of immigrant and LGBT rights and safety, the initiative negotiates and pulls apart spatial and social boundaries that are complicated and operate on multiple levels.

Each of these initiatives asserts that the safety and welfare of LGBT people in cities cannot be divorced from the social, economic and spatial conditions of urban environments. From direct acts aimed at changing discriminatory bureaucratic policy to the more consuming work of changing prevailing public opinion, these campaigns literally broaden the possibilities of movement for queers in the city. They map, both literally and otherwise, paths forward for urban social movements that are critically inclusive.

Kian Goh, AIA, LEED AP, is an architect, educator and community activist, and a partner in SUPER INTERESTING!, an architecture and sustainability consulting firm. She teaches design and sustainability at Parsons The New School for Design and the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. She is a former member of the board of directors of the Audre Lorde Project and collaborated with FIERCE on its Pier 40 campaign. She was also one of the organizers of the first LGBT contingent in the New York City Lunar New Year Parade in 2010.