By Richard A. Marcantonio

Transportation has long been at the heart of our nation’s civil rights struggle. The struggle against Jim Crow transportation was more than half a century old when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on the bus and sparked the modern civil rights movement. But today, the most prominent civil rights fights around transportation focus not on desegregation but on planning and funding of transportation in our metropolitan regions. Transit, civil rights and environmental justice (EJ) activists are asking a new question: Are low-income and minority communities receiving a fair share of the benefits of public spending on transportation in their regions?

The unfortunate answer is no. Minority and low-income populations not only are systematically denied that fair share, but often end up worse off for the expenditure of large sums on transportation improvements in their communities.

In California, bus riders have added legal strategies to their efforts to win a fair share of transportation benefits. These legal tools have included federal lawsuits in Los Angeles and the Bay Area. More recently, the success of an administrative civil rights complaint against Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) resulted in a victory for EJ communities when the federal government took $70 million in stimulus funds away from BART’s Oakland airport connector project due to civil rights violations. This article documents how efforts like these have succeeded in exposing the civil rights violations of transit funding schemes, and considers the lessons of these campaigns for transportation justice struggles in other metropolitan regions.

The Los Angeles Bus Riders Union

In 1992, The Labor/Community Strategy Center saw an organizing opportunity. Equating city buses to “factories on wheels,” it created the Los Angeles Bus Riders Union (BRU). BRU inaugurated a new era in transportation justice in the 1990s by combining bus rider organizing with legal tools. Its legal tool, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibits recipients of federal funds from discriminating on the basis of race, color or national origin. Prohibited discrimination under Title VI includes a denial of or delay in receipt of the benefits of public investment.

L.A. bus riders were overwhelmingly people of color earning under $12,000 a year. African-American janitors, Latino hotel workers and Korean garment workers were standing on overcrowded buses at the end of an exhausting day at work. Fare hikes added to the injury.

BRU turned its eyes on the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which runs both bus and rail service in Los Angeles County. In 1994, BRU was watching when MTA adopted yet another fare hike, amounting to $126 million in revenue. At the same time, MTA budgeted nearly the same sum, $123 million, to serve higher income and lower-minority suburban commuters through expansion of its Pasadena light rail line.

The inequality in the benefits and the burdens of MTA’s actions was unmistakable. Transit improvements were proposed that not only failed to benefit minority bus riders, but actually came at their expense. BRU used this evidence to file a landmark Title VI federal class action lawsuit which ended in a negotiated settlement. BRU then carefully monitored MTA’s compliance with the terms of the resulting consent decree.

BRU’s efforts resulted in more than $1 billion in bus service improvements over ten years. MTA added hundreds of thousands of hours of bus service, kept fares affordable and took steps to reduce overcrowding. BRU also paid close attention to the links between buses, public health and the environment, and as a result the MTA now runs the largest fleet of clean fuel buses in the nation.

Minority Bus Riders vs. the Bay Area’s Metropolitan Transportation Commission

The success of organized bus riders wielding Title VI in L.A. brought both hope and a new lens to the struggles of EJ communities across the country. In the San Francisco Bay Area, bus riders from Oakland to Richmond were seeing a clear, but  somewhat less direct, correlation between bus service cuts and rail expansion. In the Bay Area, unlike L.A., bus and rail service are provided by a hodgepodge of transit agencies.

somewhat less direct, correlation between bus service cuts and rail expansion. In the Bay Area, unlike L.A., bus and rail service are provided by a hodgepodge of transit agencies.

Still, the same patterns were clear. Service levels for AC Transit bus riders had fallen by 30 percent from 1986 to 2005, even as service levels for riders of BART and Caltrans rail service had more than doubled (see Figure 1).

As in L.A., bus and rail ridership is demographically very distinct—80 percent of AC Transit riders are minorities, while 50 to 60 percent of BART and Caltrans riders are white (see Figure 2).

While it was immediately clear how L.A.’s MTA played “Robin Hood in reverse,” the task facing the bus rider advocates in the Bay Area was more complicated, requiring a close analysis of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s (MTC) funding policies, transit expansion program and long-range transportation plan. That analysis showed that in each of its long-range regional transportation plans since 1992, MTC built in bus service cuts and fare hikes at the planning stage. At the same time, MTC’s plans devoted 94 percent of its transit expansion funds to rail projects, and less than five percent to bus projects. MTC was, in effect, starving bus systems of operating revenue and shifting those funds to capital projects benefiting rail systems.

While it was immediately clear how L.A.’s MTA played “Robin Hood in reverse,” the task facing the bus rider advocates in the Bay Area was more complicated, requiring a close analysis of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s (MTC) funding policies, transit expansion program and long-range transportation plan. That analysis showed that in each of its long-range regional transportation plans since 1992, MTC built in bus service cuts and fare hikes at the planning stage. At the same time, MTC’s plans devoted 94 percent of its transit expansion funds to rail projects, and less than five percent to bus projects. MTC was, in effect, starving bus systems of operating revenue and shifting those funds to capital projects benefiting rail systems.

In 2005, with analysis in hand, Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 192 (the bus drivers union) joined several minority bus riders and an EJ organization in filing a federal class action civil rights lawsuit, Darensburg vs. Metropolitan Transportation Commission. The plaintiffs asserted that MTC’s planning and funding policies prioritized rail expansion for riders who were more affluent and white while reducing levels of service for bus riders.

After trial in October 2008, the District Court issued a mixed ruling. On the one hand it found that “AC Transit has been forced to cut urban bus service to the detriment of [minority bus riders] in the past due to funding shortfalls” within the control of MTC. It also concluded that MTC could take additional steps to allocate funding in a way that would help alleviate AC Transit’s shortfalls. The Court also agreed with the plaintiffs that MTC’s transit expansion program had a discriminatory impact by excluding projects that would have benefited minority bus riders. The Court, however, ruled that MTC met its burden of proof regarding an appropriate justification for that discriminatory impact. The plaintiffs’ appeal (supported by an amicus curiae brief from Planners Network) is now pending before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Unequal Benefits and Burdens of Capital Expansion Projects

These bus rider lawsuits brought to light an important general principle: When capital expansion comes at the expense of basic transit operations, low-income communities suffer economically, as studies have shown. First, funding transit operations creates 40 percent more jobs than transit capital spending. Second, transit service automatically translates into green union jobs for bus drivers and mechanics who live in the local community. And third, operating funds have a huge economic multiplier effect. For example, investing $1 billion dollars in operating bus service yields $3 billion dollars in increased local business sales.

But beyond the economics is the fundamental question of who benefits from capital projects. Expensive capital projects often provide little benefit to low-income families who, instead, often bear the brunt of the burdens of those projects. In addition to environmental burdens, these burdens include cuts to their local transit service and displacement fueled by gentrification.

Analyzing the fair sharing of benefits and burdens by race and income has become central to EJ efforts. On top of Title VI, Presidential Executive Order 12898 on EJ adopted in 1994 requires each federal agency to “identify and address disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of its programs, policies and activities on minority and low-income populations.” This obligation extends to recipients of federal transportation funding, like MTA and MTC.

The requirement to “identify and address” inequities gave birth to the Federal Transit Administration’s policy of conducting an “equity analysis” of planned projects and then taking steps necessary to avoid or mitigate identified inequities. The purpose of the equity analysis is to determine whether low-income and minority populations are receiving a fair share of the benefits and the burdens of transportation projects and programs. The equity analysis gives bus riders a potent new legal tool.

Challenging the Oakland Airport Connector

In early 2009, more than $1 billion in federal stimulus money—two-thirds of which had to be used for capital projects for the Bay Area—arrived at MTC’s doorstep. The remainder of the funds could be spent on preservation of existing transit and new construction projects. Bus riders were eager to take advantage of that portion to shore up declining bus service which, for AC Transit riders, had declined by another 15 percent during the current economic crisis.

MTC, however, proposed to divert $70 million in transit stimulus funds to BART’s proposed Oakland Airport Connector. A three-mile, $500 million dollar project to link the airport to BART’s Coliseum station in East Oakland, the Connector would replace a $3 bus shuttle with a tram costing twice as much.

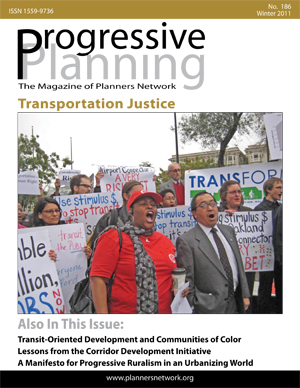

Genesis, a social justice community organizing group, turned out at an MTC meeting to protest the proposed diversion of funds. More than one hundred members packed a room seating only fifty. They did not carry the day, however, and the MTC committed the $70 million to the rail project. That might have been the end of the matter, but Genesis, and advocates from non-profits Urban Habitat and TransForm, huddled with civil rights lawyers from Public Advocates Inc. to craft a new strategy.

Like East Oakland as a whole, the demographics of the station area are predominantly minority and low income. Two neighborhoods in the station area have minority populations of over 95 percent, with poverty rates ranging from 25 percent to 33 percent. An honest equity analysis would have shown that these low-income and minority residents would not benefit from a slightly faster trip to the airport. But advocates learned that BART had not conducted any equity analysis of the Connector.

In September 2009, citing the lack of equity analysis, the groups filed an administrative Title VI complaint with FTA against BART. FTA investigated the allegations and concluded that BART had indeed not complied with the equity analysis requirement. FTA also found a range of other agency-wide shortcomings. As a result, FTA required BART to adopt and implement a comprehensive “corrective action plan” to remedy these civil rights violations.

But there was another outcome: The same $70 million that MTC had awarded to rail expansion was now back on the table. Last February, in a victory for Genesis, the communities of East Oakland and transit riders, FTA Administrator Peter Rogoff ordered MTC to reallocate those funds to shore up existing transit operations.

Lessons Learned

The success of the administrative complaint was a victory for Bay Area transit riders, but it was also a warning shot across the bow of transportation agencies all over the country. For the first time in years, the federal government was open for the business of civil rights enforcement. And organized communities fighting for a fair share of the benefits of public spending on transportation now find they have a powerful strategy to add to their toolkit.

These legal strategies also brought to the surface a template for analyzing transportation inequity that advocates in many other places are now applying. Communities are now looking at proposed transit expansion projects to determine if they will leave low-income and minority transit riders behind. And many advocates are actively asking Congress to restore federal operating assistance for transit, rather than funding solely capital projects.

As EJ advocates become more sophisticated in watchdogging transit agencies, they will continue to find effective strategies to begin to serve up fair portions of the transportation funding pie. And while the fight for transportation justice has come a long way since Ms. Parks’ battle to retain her seat, the campaign continues.

Richard A. Marcantonio is a managing attorney with Public Advocates Inc. He represents plaintiffs in Darensburg v. Metropolitan Transportation Commission and brought the administrative Title VI complaint against BART to FTA.