By Omari Fuller and Edgar Beltran

Night has fallen and you’re driving through a gritty urban center when you approach an intersection. Just as you turn right through the crosswalk a dark figure materializes before you. You slam on the brakes and stop just a foot or two away. Without pausing to acknowledge the near miss, the figure cruises to the far side of the street and disappears down the sidewalk in the murky glare of streetlights.

You’ve just glimpsed an invisible cyclist.

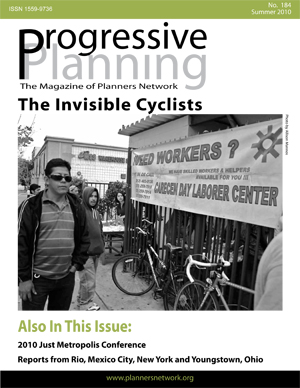

Thousands of working-class people use bicycles to traverse cities and towns across the U.S. every day. In the city of Los Angeles, this group of cyclists is as dedicated as any other, riding through the wet of winter and simmering heat of summer.

Yet you won’t see invisible cyclists at Los Angeles City Council meetings demanding bike lanes. You might not see them in the street either, as these cyclists tend to ride alone, often intermingled with pedestrians on the sidewalk, and without lights or reflective clothing. These cyclists are also often Latino immigrants, and nearly 20,000 of them in the L.A. metropolitan area use a bicycle as their main means of transportation to work

As we’ll explain in this article, this particular group has different needs than other cyclists, yet their interests receive little attention. This article will also examine a program called City of Lights, which aims to bring invisible cyclists out of the shadows using a combination of self-empowerment training and advocacy work. We found City of Lights to be a promising model for assessing the needs of an under-served group and pursuing a more equitable distribution of resources.

Profile of an Oppressed Group

Working-class immigrant Latino cyclists face a multitude of challenges that are more pronounced than those facing most other cyclists. These include sub-standard bicycles and safety equipment, no knowledge of cyclist rights, more dangerous streets with fewer provisions for safe bicycling, increased danger of bicycle theft and robbery, police harassment, lack of health insurance, minimal publicly available data on the aforementioned conditions and no political representation. We will look at these challenges in detail to make a case for the need to address the particular oppression that this group faces.

We’ll rely on tenets from critical race theory (CRT) to help structure our arguments. A key CRT tenet considers racism to be endemic and pervasive in our society and institutions. We will note subversive effects that are specifically directed against Latino identity. CRT also uses personal narratives to amplify the other voices that challenge the dominant narratives in society. Throughout this article we’ll hear the voices of those closest to this struggle. CRT also recognizes that there are unique challenges presented by the intersection of a plurality of identities related to race, class, gender, citizenship status and innumerable other characteristics. As such, we must acknowledge the multiple identities of this group of cyclists and the oppression that members of this group must endure in the form of unfair treatment as a result of those identities.

Less Money = Less Choice + More Danger

Low-wage workers have limited transportation options, compelling them to bike. Since work may not be steady enough or income high enough to be able to afford a car, or perhaps even a monthly bus pass, some are effectively captive cyclists. Limited mobility means fewer accessible job opportunities, which perpetuates low-income status.

Many can only afford to live in older, less affluent neighborhoods. In Los Angeles, these neighborhoods have older and narrower streets with no space for bike lanes. As one cyclist in the majority-Latino neighborhood of MacArthur Park put it, “I don’t know who put all those bike lanes in Santa Monica [a more affluent and less diverse neighboring city], but they did a good job, and we need that here!”

The dangerous biking conditions that result from crumbling pavement and no separation from car traffic in these older neighborhoods disproportionately affect low-income people of color. Their affordable, second-rate bicycles strain unreliably under these conditions. Bicycle helmets, which should be indispensable for hazardous urban riding, are seen as expensive and optional.

A further hazard is the high volume of truck traffic that low-income cyclists encounter when traveling to and from work in industrial areas. According to Allison Mannos, program coordinator at the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, accidents between cyclists and big-rigs are not uncommon. When injured, cyclists and their families, many of whom lack health insurance, may suffer the additional hardship of expensive medical bills.

Another infrastructure problem is the dearth of bicycle parking in high-crime neighborhoods where bikes are more likely to get stolen. Allison Mannos comments, “Even if not so many of them have a bike, at least 50 percent of them had a bike. So they’re still cyclists in the sense that many would ride if their bikes hadn’t been stolen.”

Biking while Immigrant

As immigrants, this population of cyclists experiences other challenges on top of those that arise from being low-wage workers. The many undocumented immigrants of L.A are legally barred from obtaining California driver’s licenses, limiting their transportation options by legal means on top of economic ones.

On the road, immigrant cyclists face more challenges when they have to deal with L.A. drivers. According to Adrian, a Latino student who is also active in the burgeoning Los Angeles bicycle movement, “Older Latino immigrants don’t know their rights. Due to language issues or being misinformed, they let cars push them to ride literally right next to the curb, almost pedal striking it.” (Pedal striking is bike lingo and refers to the dangerous situation arising when the pedal strikes something, which can cause the bike to swerve wildly and the cyclist to be thrown off the bike into traffic.) Thus, although the California Vehicle Code states that bicycles have all the rights and responsibilities of vehicle drivers, including full use of the roadway, ignorance of the law contributes to immigrant cyclists being intimidated and forced into even greater danger at the margins in the gutter and on the sidewalk.

Biking while Latino

Does being Latino contribute to being stopped by police while biking? Although the Los Angeles Police Department doesn’t release data on police stops by race, we know that one of the few places they’ve set up stings to enforce a no-bikes-on-sidewalk law is in the MacArthur Park area where around 80 percent of residents are Latino. Also, adult cyclists are not required to wear a helmet, but comments like “I’ve been stopped by the cops three times for not wearing a helmet,” were common when we interviewed working-class Latino cyclists. In these instances, possible police targeting compounded by ignorance of the law leaves Latino cyclists vulnerable to mistreatment that other groups may not face.

There is little opportunity for this group to redress these and other oppressions due to their lack of representation in the civic arena. Limited English language proficiency and a community-wide mistrust of the authorities help explain why it is uncharacteristic of this group to walk into City Hall and demand better police treatment or more resources for safe biking in their neighborhoods. Complicating any effort to make such demands is the absence of accident statistics or data on police stops and ticketing that might illustrate the degree to which heightened risks affect this particular group of cyclists. That is why, according to Allison Mannos, “Any data at all, quantitative or qualitative, that we can get on the experiences of this population is a good thing.”

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

Because they ride at the margins with little evidence of their plight and without a voice in the civic arena the public is oblivious to these invisible cyclists. Critical race theorists suggest that for every disadvantaged group, another group receives some advantage. We wonder who benefits from the challenges confronting invisible cyclists. One possibility is law enforcement, which increases its revenues and police power by ticketing and detaining members of this population on questionable grounds. Motorists are another group of beneficiaries who gain in time and convenience what invisible cyclists lose in safety. In other neighborhoods of L.A. that have better amenities, residents and bicyclists may benefit from infrastructure improvements that should be shared with less affluent parts of the city.

More work should be done to identify the beneficiaries in this scenario and to eliminate the incentives that perpetuate it. In the meantime, let’s consider the current efforts being taken on behalf of the invisible cyclists.

Illuminating the Shadows: Critical Race Theory and Advocacy

City of Lights is a program of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition that was created to reach out to working-class Latino immigrant cyclists who have limited English proficiency. The program is working to ameliorate the oppressions that affect this group through advocacy and education, in the form of community workshops on safety issues, legal rights and bike maintenance.

City of Lights bike safety workshops educate cyclists on the rules of the road and safe riding techniques, essential knowledge for the dangerous areas where these cyclists ride. The educational programming is reinforced with the provision of donated safety equipment such as lights, helmets, locks and bike maps to cyclists for whom the expense of such equipment would be too great. A bike maintenance workshop might stress the importance of maintaining the proper tire pressure, which not only helps prevent having a dangerous blow-out while riding in traffic, but can save cyclists money by avoiding the costs of tire repair or replacement and travel delays. These workshops are hands-on and designed to foster self-reliance, teaching cyclists how to maintain their bikes against the strain of riding on L.A. streets. Some workshop participants have expressed that their new bike maintenance skills could open a door to employment opportunities or business ownership, which could have a very positive effect on their income. Legal rights workshops are designed to curtail the number of unwarranted citations.

Data backs up the advocacy efforts of the City of Lights program. As Allison Mannos describes, existing cyclist data provides little information on Latino immigrant cyclists, who may not feel comfortable responding to conventional bike surveys. City of Lights tries to rectify this by conducting their own surveys with questions that capture the difficulties and experiences of this group of cyclists. Quantitative data is of interest, but collecting personal narratives also affords invaluable insights. For example, asking cyclists about their riding experience in the U.S. and in their country of origin can reveal a person’s economic, social and environmental motives for riding.

The next advocacy step is to raise general awareness of invisible cyclists. To that end City of Lights staff attend conferences to highlight their data findings and workshops in the low-income Latino immigrant cycling community. They also push the Los Angeles City Council and municipal departments to provide more bike lanes and bike parking where these cyclists live, work and ride and they communicate with law enforcement to request data on how often and why invisible cyclists are stopped and cited, potentially revealing and deterring oppressive police tactics.

By focusing on invisible cyclists and establishing their concerns as worthy of attention, the City of Lights efforts build on another tenet of critical race theory: centering and validating the experiences of marginalized people. According to Allison Mannos, the key is to rely on the narrated experiences of members of the specific group to identify their needs, rather than imposing on them external ideas about what their needs are. “When we talked to these cyclists,” says Mannos, “we found out they aren’t that into racing or wearing spandex, but they are interested in having a place where they can work on their bikes and see other people like them. Our priority now is to create spaces like that where they can build their own cycling community.”

Bringing invisible cyclists together and out of the shadows should help address their numerous challenges and, hopefully, make your next encounter with them far less harrowing.

Omari Fuller and Edgar Beltran are master’s candidates in the Department of Urban Planning at the UCLA School of Public Affairs.