By Marie Kennedy and Chris Tilly

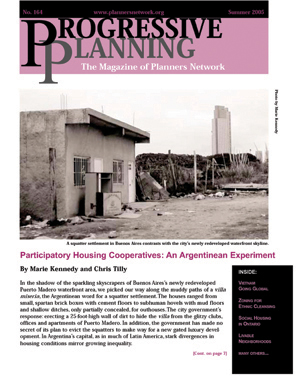

In the shadow of the sparkling skyscrapers of Buenos Aires ‘s newly redeveloped Puerto Madero waterfront area, we picked our way along the muddy paths of a villa miseria, the Argentinean word for a squatter settlement. The houses ranged from small, spartan brick boxes with cement floors to subhuman hovels with mud floors and shallow ditches, only partially concealed, for outhouses. The city government’s response: erecting a 25-foot-high wall of dirt to hide the villa from the glitzy clubs, offices and apartments of Puerto Madero. In addition, the government has made no secret of its plan to evict the squatters to make way for a new gated luxury development. In Argentina ‘s capital, as in much of Latin America, stark divergences in housing conditions mirror growing inequality.

But, in Argentina —as in much of Latin America today—scrappy grassroots housing movements are working hard to move beyond survival and begin closing economic and social gaps. Slum-dwellers, squatters, homeless people and tenants have opened varied fronts in a struggle for decent, affordable housing. A particularly Argentinean contribution to the mix is a small but determined group of movements committed to horizontalidad—horizontality, meaning highly participatory democracy and consensus decision-making. Daniel Betti, the architect, urban planner and Buenos Aires city councilor who was our guide through Villa Costanera Sur, gave us a crash course on one such current, a cooperative housing movement that has launched 5,000 families on the way to building housing co-ops.

According to Betti, one in seven of Buenos Aires ‘s 2.8 million inhabitants is experiencing a housing emergency. This includes 120,000 living in villas miserias, and 140,000 squatting, primarily in abandoned industrial buildings. Tens of thousands more live in government subsidized homeless hotels, often ten to twelve to a room. Others live in “legal” but barely livable housing or on the street.

Crisis and Resistance

Argentina ‘s poor and working-class residents have lived through economic hard times since the mid-1990s. President Carlos Menem, who governed from 1989-99, presided over neoliberal free trade and privatization policies that resulted in waves of layoffs and plant closings. But the country’s powder keg exploded in 2001, when investor panic and devaluation of the peso suddenly wiped out much of the assets and purchasing power of Argentina ‘s large and, until then, prosperous middle class. In two days of massive street demonstrations, Argentina ‘s people drove out then-president Fernando de la Rua. A series of short-lived caretaker presidencies followed, and finally, in 2003, elections brought the current president, center-left Nestor Kirchner, to power. Kirchner has flaunted populist rhetoric, taken a tough bargaining line with international lenders seeking to collect the country’s huge debt and shunned repression of protestors. But, he has stopped short of supporting the development of a grassroots “social economy,” leading many in the horizontal left to view him with skepticism.

The 1990s incubated a variety of new types of organizations, such as community-based unemployment movements and groups of workers occupying their shuttered factories—in many cases, at least initially, experimenting with principles of horizontalidad. The 2001 crisis then led to an exponential increase in these and other organizations, although levels of participation have subsided since their peak.

Despite limited economic recovery since 2001, misery remains widespread. A nighttime walk through Buenos Aires reveals armies of cartoneros —cardboard scavengers digging through garbage bags to retrieve cardboard they can trade for a few centavos. At the same time, the city’s rents are climbing, shooting up at an annual rate of 27 percent in May, with some lease renewals as high as 100 percent. While desperate families continue to crowd into vacant factories, young professionals are buying and rehabbing them, pushing rents up. Spokeswoman Noemí Caracciolo of the Tenant Association of the Argentine Republic protested, “We want a rent freeze,” but glumly admitted, “we don’t know to what extent the government will be able to respond to us.”

A Cooperative Way Out?

Argentina has a long cooperative tradition, extending back to agricultural and consumer cooperatives formed early in the last century. So, it’s not surprising that the city of Buenos Aires, which is a freestanding jurisdiction like the District of Columbia, passed Law 341 in 2000, which encourages formation of housing cooperatives. What’s more surprising, according to City Councilor Betti, is that nobody used the law for a year. “In 2001, I was hired onto a team for the Housing Institute,” explained Betti, who was not elected councilor until 2003. “I pulled the law out of a chest,” he said with a broad smile.

Law 341 provides for government-financed, low-interest thirty-year loans to finance land acquisition and construction. It also mandates participatory design and planning by the members of each co-op and allocates limited funds for technical assistance. With a boost from the charismatic, high-energy Betti, use of the law has taken off. When we spoke in June, there were over 200 housing co-ops in Buenos Aires, encompassing 15 to 16,000 persons. Most are in the early stages. Twenty co-ops are engaged in construction and forty others have acquired land; none have completed their projects yet.

Housing co-ops range from ten to fifty families, and include groups from the villas miseries, squatter groups and groups in homeless hotels. There is even a group of forty worker-owners at the worker-occupied Hotel Bauen who can’t afford housing and are quietly camping out with their families in rooms on the upper floors of the hotel (during our stay at that hotel we periodically saw unaccompanied children taking the elevator to the top floor). In describing how the formation of cooperatives has moved these groups forward, Betti remarked, “All of these groups were resistance movements in the sense that they were asking for subsidies from the government. Our task is to help them move from resistance to self-management, to making a positive proposal.” He had few good words for what Argentineans call “assistentialist” movements that simply protest in order to continue a flow of government aid, without fighting to change the conditions that make the aid necessary. “Assistance from the state turns you into an idiot,” he growled. “The struggle must be to transform people, not to get a check.”

The Struggle to Transform People

That’s where the participatory process comes in. The law is vague about the nature of participation and different organizations have approached participation in very distinct ways. For example, the Argentine Communist Party’s Piquetero Branch ( piqueteros is a generic name for movements of unemployed people who use street and highway blockages to press their demands) builds housing rapidly, with little emphasis on participation along the way, according to Betti and Maiqui Pixton, a social psychologist on one of the technical assistance teams working with housing co-ops. “That’s because the Communist Party is part of the political establishment—they have a bank!” Betti noted. Pixton added that often when worker cooperatives develop housing, one leader drives the process and makes the decisions. Betti characterizes this approach as “vertical work, though it may appear horizontal. The hierarchy of the organizations gets reproduced in the housing work.”

On the other hand, said Pixton, “Some organizations work with cooperatives in a long process of social development and maturation before they start developing housing.” The Movement of Tenant Squatters is one such organization. “They started out by occupying buildings, demanding to either receive credit or be given the buildings, and forming cooperatives,” said Soledad of the Unemployed Workers’ Movement of La Matanza, a horizontal piquetero organization based in Buenos Aires’s industrial ring (like many horizontal activists, she prefers to just be identified by her first name). “But they discovered that once people got the title to the housing, they dropped out. So now they organize a cooperative first, do consciousness-raising and only then take the building.”

Betti and his allies, including social psychologist Pixton, try to stake out a middle ground between these two extremes. “We work on self-management without preconditions,” commented Pixton. “We don’t demand that people be at a certain point. The housing emergency that they face makes it worthwhile to work simultaneously on social development and the housing itself.” This is especially true because government promises of funding can evaporate at any moment. At the same time, she added, “We work on having everybody make decisions together. That way, they are equipped to go beyond housing to work on education, health, jobs…whatever other issues confront them.” Betti chimed in, “Housing is a pretext. Of course it’s a necessity, but it’s also to create a focus that can lead to empowerment and the capacity to achieve future goals.”

What Role for Planners?

The technical assistance teams play a critical part in guiding this process. The teams, which act as independent contractors hired by groups forming co-ops, include architects, social scientists, lawyers and accountants (as in much of Latin America, Argentina does not have a profession that calls itself “planning”). Maiqui Pixton’s team, with eighteen professionals who work with fifteen co-ops, is the largest. Ten percent of the government credits to the cooperatives can in theory go to pay the professionals, but “the money comes in drips,” said Pixton. “The reality is we can’t live on the fees and have to have other jobs.

Pixton identified the teams’ key challenge as “breaking with the hegemony of the sciences. It’s not just a question of knowing participatory methods,” she elaborated, “but understanding that people can make their own decisions, that they can manage projects themselves. We have to accept that people may come up with a different answer than we do. When we say that we are working for transformation, we include ourselves!” Betti added, “Architects make plans, but people don’t necessarily understand how to read them. We found that we have to make the units big enough that people can design their own space.” The solution has been 2-story-high “shells” within which each family can place rooms to meet its needs.

Another challenge is knowing how to combine support for the cooperative groups with pressure to move toward true self-management. “Some groups move rapidly to functioning autonomously,” Pixton said, “and some stay dependent. Our task is to let them know they’re not alone, but the decisions are theirs. It’s a delicate balance.” The goal, she said, is “to always encourage that everybody gives their opinion and that all opinions are valued. Often it doesn’t seem like they’re paying attention to us,” she mused. “But then you see that when they work on their own, they’re reproducing those practices—everybody gets to speak, all opinions are valued—and so you see that theyhave learned.”

The government of Buenos Aires itself does little to help this process. “We have a society where a lot is simply dictated,” Pixton observed. “When the government gives a benefit, it imposes it, without asking people how it might work better. You’re supposed to consider yourself lucky if you get an apartment, even if it’s in appalling shape and doesn’t meet your family’s needs.” Moreover, the pervasive institutional corruption trickles down. “We understand why acts of corruption happen in the cooperatives,” said Pixton. “They’re imitating what they see around them. And they’re economically desperate—if our kids didn’t have anything to eat, how would we act? Still, even when they are in a state of poverty and desperation, you can demand that people act honestly, transparently and responsibly.”

This is What Democracy Looks Like

Pixton lit up the most when describing how involvement in the housing co-op process led to broader and deeper transformations. She told the story of a co-op president who started organizing with neighbors in a tenement several years ago. “He told me, ‘At that time, I didn’t know how to talk! I couldn’t talk in a way that other people understood—I couldn’t speak for myself, I was just a beast of burden. I had to learn to communicate in order to carry out this planning process.’ To get language is to also get freedom,” Pixton remarked. “If you speak for yourself, you can also think for yourself.”

Another frequent transformation is women who leave a battering situation due to their involvement in the cooperative process. The combination of group support and increased self-confidence developed through action makes the break possible. “And those are the women who fight the hardest against any authoritarianism in the group,” Pixton pointed out.

Democracy isn’t always pretty. As we toured the Costanera Sur villa with Betti, he got a call on his cell phone about a dispute between two of the largest housing cooperatives on what organizing strategy the Federation of Housing Co-ops should adopt. “These struggles always come up in the social sector,” he remarked. “The important thing is not to hide them; as the saying goes, ‘Don’t put French perfume on shit.’ If the process were authoritarian, there wouldn’t be any problem. One person would decide, and the rest would have to go along. But if it’s democratic, there’s always going to be disagreements.”

Participatory Legislation

Betti describes Law 341 as a good law, “but only a basic law.” He is currently helping to draft a broader municipal housing ordinance that would declare a state of housing emergency and provide significantly expanded funds for self-managed housing development. And naturally, he’s organizing a participatory process to decide what will go into the legislation. The model for this process is an earlier process to draft a law establishing neighborhood-level governments—a first for Buenos Aires, and due to go into effect starting with local elections this fall. “That law was written by forty-seven neighborhood assemblies!” Betti exulted. (Scores of self-organized neighborhood assemblies sprang up in Buenos Aires neighborhoods, especially middle-class ones, during the 2001 crisis.) “But that was the middle class. This time, with the housing law, we’re involving the poor—because they know their own needs.”

At the time we spoke, workshops that included cooperative members and technical teams were holding meetings to identify priorities and areas of consensus for a draft housing law. Betti hoped to complete the process by the end of the summer. “So far, we don’t have the votes,” he acknowledged. The left bloc in the city council includes only eight councilors out of sixty. “But we have people who will fight for it, because they feel that it is theirs.” He noted that because politicians have been so discredited, mobilization can make a big difference. Betti’s ambitious vision is to build from this housing self-management law to a complete housing law, and from a Buenos Aires statute to laws across the country. “We have a saying in this country,” he said with a wink, that “in Argentina, God is everywhere, but he’s paying attention to Buenos Aires.”

Betti’s plan also depends on getting re-elected this October. “I have to find a party to run with,” he said. Candidates must be part of the list of some officially recognized party, and although the Argentine government recently approved 546 new parties, none of them appeal to Betti (and neither does the party he ran with in 2003). “I’m thinking of forming a new little party with some others, Liberatory Self-Management of Buenos Aires (ALBA). And if I don’t win, that’s OK. I’ll still keep doing what I’m doing—I always have.”

Organizing 15,000 cooperative members marks a small step toward meeting the needs of 400,000 Buenos Aires residents living in a state of housing emergency. Winning a bigger, better city housing law will help. But perhaps even more important than the law itself is the process of organizing and participatory planning that is training a cohort of thousands of new activists. When we last saw Daniel Betti he was even more excited than usual. “Something really good happened yesterday in that villa we visited,” he announced. “All the block representatives came to my office together. They said they’ve decided they don’t just want to fight against expulsion from their land. They also want to launch a cooperative housing project!” The spirit that moves ordinary Argentineans from resistance to production is a powerful one—one worth watching as a positive example not just for Latin America, but for the rest of the world as well.

Marie Kennedy is professor emerita of community planning at the College of Public and Community Service, University of Massachusetts Boston and a member of the Planners Network Advisory Committee. Chris Tilly is a professor of regional economic and social development at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. Both have worked in Latin America solidarity movements for many years. They visited Buenos Aires in May-June 2005.