By Jennifer Ridgley and Justin Steil

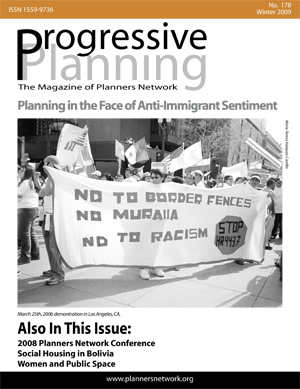

In July of 2006, the city of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, became a focus of national media attention when its city council approved the Illegal Immigration Relief Act Ordinance (IIRA) proposed by Mayor Lou Barletta. Allegedly targeting “illegal” immigration, the ordinance established a $1,000 a day fine on landlords who rented to people who were in the country without authorization, and enabled the town to revoke the licenses of businesses who hired the undocumented. The first version of the IIRA also declared English the official language of the town and prohibited the publication of city materials in any other language. The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund and the American Civil Liberties Union immediately filed a lawsuit, arguing that the ordinance was preempted by federal law and would lead to discrimination against Latino residents, regardless of immigration status. Implementation of the ordinance was halted by a federal district court injunction and eventually struck down on the grounds that it was preempted by the federal government’s exclusive control over regulation of immigration, and the city subsequently appealed. Still, passage of the ordinance alone has already had significant effects on Hazelton.

Hazleton’s ordinance is one of the better known of more than 1,000 state and local bills regarding immigration introduced in 2006 and 2007. As in Hazleton’s tenant registration provision, many of these statutes seek to control immigration by regulating the use of public and private space. These efforts to establish divisions based on immigration status are tied to a long history of housing and land use policies used to differentiate among residents based on perceived race or ethnicity. The emphasis of Mayor Lou Barletta that Hazleton is an “all-American” small town under siege by unprecedented “illegal” immigration obscures the city’s history of immigration and labor conflict. This article highlights some of the parallels between Hazleton’s experience at the turn of the last century and at the turn of the most recent one, It also examines Hazleton’s current situation in light of its history as a city that emerged largely because of efforts to control immigrant laborers in the anthracite coal mining industry in the nineteenth century.

Immigrant Labor and Ethnic Hierarchies

After anthracite coal was discovered in central Pennsylvania in the first decades of the nineteenth century, local entrepreneurs founded the Hazleton Coal Company in 1836. The town of Hazleton was incorporated fifteen years later with a population of about four thousand. As industrial growth accelerated through the second half of the century and demand for anthracite increased, coal breakers (the towers that break chunks of coal into smaller pieces) sprouted quickly from new mines surrounding the city and coal companies throughout the region began recruiting migrants for the dirty, dangerous work. Hazleton grew to a population of 12,000 by 1890 and 25,000 by 1910 before peaking at 38,000 in 1940, and then beginning a sharp decline.

At first, companies sought recent immigrants from England, Scotland and Wales, many of whom already had experience working in the coal industry. These workers were favored for the highest skilled and highest paid positions, while Irish migrants were relegated to the more dangerous and lower paid jobs. But no matter their position, mine workers rarely prospered, facing instead the constant threat of injury or death on the job. When signing up immigrants from Great Britain and Ireland became more and more difficult as migrants eventually became increasingly resistant to the exploitation of their labor in such a low-wage, high-risk industry, mining companies established active recruiting networks across Southern and Eastern Europe, constantly seeking a more malleable workforce.

Employers also produced and exploited ethnic hierarchies in the mines to drive a wedge between employees and distract public opinion away from developing sympathy for the miners and their dangerous work. Workers were paid by the piece, measured variously by the ton, the car or in linear yards. Rates varied across mines and even within the same mine. The allocation of unequal responsibilities, reliance on uneven measures of production and the payment of varying wage scales even among similarly situated workers within the same mines were tactics that served to forestall organizing.

The Spatial Organization of Social Life around the Mines

A crucial part of this strategy of division was the spatial organization of social life around the mines. To accommodate and control the growing workforce on which the booming industry relied, mining corporations in and around Hazleton built company towns and laid them out to represent and reinforce the social divisions on which the industry relied. It is estimated that two-thirds of the housing in the anthracite coal region of central Pennsylvania in the late nineteenth century was owned by mining companies. Company managers and owners, who were usually of English descent, generally lived in large houses near the center of town where the hotels, doctors’ offices and Episcopal Church were located. The Irish foremen and the Southern and Eastern European laborers were relegated to smaller houses on the “patches,” the small settlements that the mining corporations built up around the company store and closer to the polluting anthracite breakers in which they worked.

The spatial divisions of social life limited the interaction of different ethnic groups outside of the ethnic hierarchy in the mines. The organization of the towns embedded social hierarchy in space, from proximity to doctors to proximity to cemeteries, and segregated by ethnicity. Each ethnic group created its own churches, beneficial societies and fire companies and the communities largely turned to co-ethnics for support in the face of a hostile society. These conditions made it incredibly hard to unite workers in a truly multiethnic union that might be able to improve worker safety or increase wages. These difficulties were heightened by mining companies’ violent suppression of labor unrest, including public hangings of labor leaders and threats from armed militias formed by the corporations.

The 1897 Lattimer Massacre and the Forging of Worker Solidarity

A turning point in efforts to organize workers across ethnic lines took place just outside Hazleton in 1897. In August, thirty-five immigrant workers at a nearby mine went on strike against an arbitrary rearrangement of work schedules requiring two additional unpaid hours of work. The supervisor ordering the new schedule then hit one of the workers with an ax handle and over the next two days more than two thousand miners joined the strike, demanding the supervisor’s discharge. The strikers created a temporary local chapter of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) that had a Hungarian president and an Italian vice president. Their demands included equal pay for immigrant and native-born miners and an end to the company store as well as the right to select and pay their own physician.

The strike continued to gain momentum through August and into September. On 10 September, unarmed workers marched towards the company town of Lattimer to encourage miners there to join the strike. The Coal and Iron Police fired indiscriminately into the crowd, killing twenty-two and injuring thirty-six more, mostly Slovakian and Polish immigrants. The massacre contributed to a newfound understanding among native-born miners of the need for solidarity with their immigrant co-workers and enabled the UMWA to become a more integrative force among workers.

National Security and Immigration Control

While immigrant and native-born workers of varying ethnicities in the mines were able to find increasing solidarity, economic depression in the 1890s followed by the social upheaval after World War I generated heightened nativism. At the same time, the Russian Revolution increased fears about national security and corporate leaders worried about growing union power. In 1919, a number of U.S. politicians called for a “one-language nation” and groups like the National Security League established study groups to train teachers in inculcating “Americanness” in their immigrant students. The Mayor of Gary, Indiana, declared that the response to the perceived threats to national security was deportation.

These fears about national security and immigration led to the “Palmer Raids” against immigrants associated with the labor, communist or anarchist movement. Attorney General Palmer turned the popularity of his anti-immigrant stance into tentative plans to run for the presidency. Speaking to the Georgia delegation of the Democratic National Convention, Palmer said, “I am myself an American and I love to preach my doctrine before undiluted one hundred percent Americans, because my platform is, in a word, undiluted Americanism.”

The 2006 Illegal Immigration Relief Act

Almost a century later, immigration control is again linked in political discourse to contemporary fears about national security, and politicians like Hazleton’s mayor have seized upon anti-immigrant sentiments to seek higher office. In establishing his platform, Mayor Barletta emphasized that “Hazleton is small-town USA…an all-American city” that must be defended from the dangers of illegal immigration.

But just three short years ago, Barletta and others were excited by the arrival of immigrant entrepreneurs who were helping revitalize Hazleton’s declining downtown. What changed?

As Hazleton has grown over the past decade as a manufacturing and logistics center, employers have needed more workers. Latino immigrants and citizens have moved to Hazleton to take advantage of employment opportunities, high vacancy rates and modest home prices in Hazleton’s downtown. As a result, the city has undergone a significant demographic transformation since 2000 from a population of 23,000 people that was 93 percent white and Anglo to an estimated 33,000 people, one-third of whom are Latino. Ironically, as the Latino population increased between the 1990 and 2000 Census, the proportion of foreign-born residents in Hazleton actually decreased, since many of the recent Latino arrivals are U.S. citizens born in Puerto Rico or young people born in historic immigrant gateways like New York.

These recent arrivals found a city with a declining population and plummeting property values. The collapse of the coal industry and departure of the textile industry in the second half of the twentieth century had led to persistent disinvestment and accelerating class divisions between the city and its suburbs. These transformations contributed to general anxiety among the older residents who remained in the city about their economic future and their control over the place they called home. Hazleton’s IIRA played into the economic and social anxiety that the changing geography of capital investment in the area had created and brought tensions to the surface in heated discussions over the meaning of quality of life, immigration and legality.

Control over Urban Space

In his speech to the Hazelton City Council introducing the legislation, Mayor Barletta argued that the best way to deter immigrants was through control over residential space by making it impossible for immigrants to find a place to sleep at night. Clarifying the strategy of turning to landlords as the “first line of defense” in controlling the space of the city, Barletta stated: “Let me be clear. This ordinance is intended to make Hazleton one of the most difficult places in the U.S. for illegal immigrants.”

The housing regulation, a seemingly race-neutral policy, could be used to harass Latinos by requiring the constant production of various forms of documents in order to access basic human needs for shelter and work. Even though the ordinance has never been implemented, its passage has had significant impacts on the residents of the town, including Latino citizens, legal permanent residents and the undocumented.

The Impacts of the Ordinance

Members of La Casa Dominicana of Hazleton have expressed fears that they will be forced to produce citizenship documents to complete routine transactions in the city and concerns about the safety of their children in school. Latino residents from surrounding towns have expressed reluctance about coming into the city because of concerns that they will be stopped unnecessarily by police. Residents have expressed fears that if they let family members or friends stay with them and it turns out that the guest is out of status—even if they unaware of this—they may face legal consequences for “harboring” the undocumented. In the face of all this uncertainty and insecurity, many Latino residents have left.

The ordinance’s threat to restrict access to the spaces crucial to everyday life has created fear among Latino residents. It has furthermore reinforced the exclusionary social identities that the conflict over the ordinance helped create and perpetuated the spatial segregation on which such exclusionary identities thrive.

The Implications of the Ordinance

Throughout its history, differential access to space has been used to construct and reconstruct social difference in the U.S. Local authority over housing codes, bylaws and zoning regulations has long been used to reinforce segregation, maintain a marginalized labor force and reinforce racialized boundaries of national membership.

In Hazleton in the nineteenth century, the differentiation of space was used to reinforce ethnic hierarchies and control a divided immigrant labor force. Today, local immigration ordinances such as the IIRA are part of a larger strategy advanced by national anti-immigration groups to make life for undocumented, and arguably, documented, immigrants more and more difficult so that they will eventually leave or “self-deport.” In this attempt to make it impossible for some to live in the U.S., the first and most effective step is once again to exercise close control over space, over the places people live, work and recreate. This control over what we consider basic entitlements of citizenship—freedom of movement and access to public accommodations—changes the space of the city and who has access to it.

The proliferation of ordinances such as Hazleton’s IIRA encourages segregation and raises significant fair housing and civil rights issues. The ordinances also have important political ramifications for urban governance, and tremendous impact on issues of social equity, neighborhood cohesion and equal access to public space and services. Looking at Hazleton’s history reveals that these efforts are not new, but are intertwined with the complex historical relationship between space, immigration and labor.

Just as immigrants and the native born in Hazleton at the end of the nineteenth century came together to resist increasingly violent repression by mine owners, immigrants and the native born in Hazleton today are also forging new alliances. While Mayor Barletta remains overwhelming popular among voters, there is a growing resistance to the anti-immigrant politics he represents. In response to the ordinance and the discrimination it generated against Latino residents, local leaders organized the Hazleton Area Latino Association and the Hazleton Hispanic Business Association, which were both plaintiffs in the successful lawsuit against the city.

Undeterred by the hostile climate and believing that political participation is essential to gain equal representation, an unprecedented number of both native- and foreign-born Latino citizens ran for elected offices in 2007, including to the city council and school board. While none were elected, their candidacy is a first step toward making Hazleton’s local government represent its recent migrants in addition to its earlier ones.

The miners around Hazleton a century ago overcame efforts by employers to foster divisions along ethnic lines and found strength in their unity. Similarly, recent arrivals in Hazleton are forging a newfound solidarity regardless of whether they are citizens, legal residents or the undocumented. Their increasing organization has empowered them to challenge the mayor’s efforts to demonize and drive out the undocumented, and the recent arrivals are indeed changing the face of Hazleton as generations of immigrants before them did. As migration has shifted to smaller towns and rural areas across the country, new allegiances are forming in these communities, expanding what it means to be part of “small-town America.”