By Marie Kennedy

In South Africa, residents of Soweto are smashing water meters and taking Johannesburg Water to court in protest against prepayment meters, which they claim are unconstitutional (the South African constitution guarantees water as a human right).

In Michigan, activists striving to prevent bottling companies from further water takings are seeking legislative oversight and a constitutional amendment to protect against Great Lakes water diversions or exports.

In Plachimada, Kerala, India, Adivasi women started their years-long dharma, or sit-in, in 2002 to prevent the local Coca-Cola bottling plant from stealing and polluting their water. This year, Kerala banned colas, and Coke Pepsi Free Zones are spreading across the country.

From Atlanta to Cochabamba to Buenos Aires, people outraged at steeply rising water rates coupled with lousy service are driving out private water companies and insisting on public accountability for the management of this most precious resource. In practically every country in the world today there are clashes over water—who owns it, who controls it, who needs it.

But you don’t hear much about the role of water in the Mideast, particularly in the context of the armed confrontations between Israel and their Arab neighbors. Yet Israel’s expansionist program is as much about water as it is about a clash of religion or security. For Israel and the other countries of this arid region of the world, control of sufficient water is security.

Water, Israel’s History and the Occupation

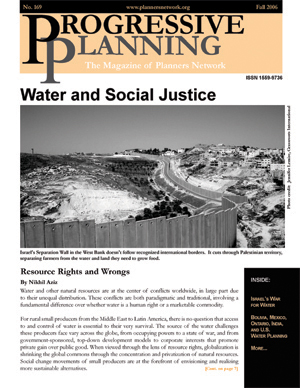

Many believe that water was the underlying reason for the invasion and occupation of the West Bank in 1967. Among Palestinians, it is understood that the location of the apartheid wall (security fence in Israeli terminology) has more to do with continued Israeli control of the Western Mountain Aquifer than with security. The possibility has been raised that a major reason for the removal of the settlements in Gaza was that the Coastal Aquifer upon which these settlements and all of Gaza have depended became almost useless due to over-pumping and pollution. Some believe that the reason for the widespread destruction and de-occupation of Southern Lebanon in the recent war was to realize the age-old hope of Zionists to include the southern bank of the Litani in the state of Israel.

So, what is the basis for these speculations?

Water has been a key element of local and regional politics in the Middle East for centuries. The early Zionists recognized that water was critical to the realization of their dreams. In a proposal to the League of Nations in 1919, the World Zionist Organization delineated borders for the future Jewish homeland based on watershed boundaries so as to include the headwaters of the Jordan River, the lower Litani River in Lebanon and the lower reaches of the Yarmouk River. In the 1947 partition plan, none of these areas were included in the new state of Israel. Israel now controls all these areas, however, with the exception of the Litani River. In 1973, Israel’s former prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, reiterated the importance of expanding Israel’s borders based on access to water: “It is necessary that the water sources upon which the future of the Land depends should not be outside the borders of the future Jewish homeland. For this reason we have always demanded that the Land of Israel include the southern banks of the Litani River, the headwaters of the Jordan and the Hauran Region from the El Auja spring south of Damascus.”

The National Water Carrier, designed to irrigate the Negev Desert in the south of the country with the water from the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River, was completed in 1964. Israel began to withdraw water from the Jordan, soon taking more than its previously agreed-upon share. Syria and Jordan responded by starting construction of diversion schemes of their own. In 1965, Israel attacked the Arab construction sites and the ensuing border conflicts culminated in a full-scale war in June 1967. Ariel Sharon, the general in charge of the war, later commented, “People generally regard 5 June 1967 as the day the Six-Day War began. That is the official date. But, in reality, it started two-and-a-half years earlier, on the day Israel decided to act against the diversion of the Jordan.” Whether or not water was the primary cause of the Six-Day War, the result of the war for Israel was control of and direct access to significantly increased water resources—estimated to be a 50 percent increase in freshwater supplies. As Vandana Shiva writes in her book Water Wars, the result of the war “was in effect an occupation of the freshwater resources from the Golan Heights, the Sea of Galilee, the Jordan River and the West Bank.”

Confiscation of almost all West Bank wells was one of the first military orders of the occupation and, until 1982, the military controlled West Bank waters. Now the Israel water company Mekorot is in charge. Management has deeply discriminated against Palestinians and has been wasteful of water when it concerns Jewish settlements. No new Palestinian wells have been permitted for agricultural purposes since 1967 and very few have been permitted for domestic purposes. Israel has set quotas based on 1968 usage of how much water can be drawn by Palestinians from existing wells. When supplies are low in the summer, Mekorot closes the supply valves to Palestinian towns and villages, but not to illegal Israeli settlements. Settlers continue to fill swimming pools and water lawns while Palestinians lack water for drinking and cooking. Furthermore, settlers receive heavy subsidies for water to promote agriculture while Palestinian farmers pay the same amount for irrigation water as for drinking water. Twenty-five percent of West Bank Palestinian villages are not connected to water service. When tensions are high and closures common, it is almost impossible for water tankers to enter Palestinian areas and for villagers to get to nearby wells.

Israeli-Palestinian Water Inequities

According to most estimates, Israel uses 73 percent of the water available from West Bank aquifers and West Bank Jewish settlers another 10 percent, leaving West Bank Palestinians with 17 percent. Israelis get about 350 liters of water per person per day while Palestinians get just seventy liters—less than the 100 liter minimum standard of the World Health Organization. About a quarter of all of Israel’s water comes from the Western Aquifer and over a third comes from the Jordan Basin.

The occupied West Bank sits on top of 90 percent of the replenishment area feeding the Western Aquifer, which flows underground from the highlands of the West Bank to the lowlands of Israel. A separate Palestinian state on top of the Western Aquifer would give the Palestinians upstream claims to the lion’s share of this water. Israel would have downstream water rights, but those rights would be limited, like Mexico’s water rights to the Colorado River. And if the eastern border of a Palestinian state were to be along the Jordan River, Palestine would have downstream water rights to the Jordan. Such considerations no doubt led former Agriculture Minister Rafael Eitan to declare that relinquishing control over water supplies in the Occupied Palestinian Territories would “threaten the Jewish state.”

Water and the Wall

This concern about water may explain the route of the apartheid wall. As Noam Chomsky points out, if the wall were really a security wall it would be built “inside Israel, within the internationally recognized border, the Green Line established after the 1948-1949 war.” But, the wall that is being built follows quite a different path. Elisabeth Sime, a director of CARE International in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, put it succinctly: “The route of the wall matches that of water resources, the latter being conveniently located on the Israeli side.”

When completed, the wall will divide the West Bank into a northern and a southern section. Writing in Stop the Wall in Palestine, Abdel Rahman Al Tamimi, an engineer with the Palestinian Hydrology Group, notes that the wall “will make the upstream of the aquifer inaccessible to Palestinians ensuring that Israel will control both the quantity and the quality of the water.” He goes on to speculate about what this will mean to any final status negotiations.

The aquifer is under the most fertile lands in the West Bank, thus water usage in the area is closely tied to agriculture. Inaccessibility to the lands because of the Wall will deem these lands dried and useless in just a few seasons; the agricultural sector will first diminish and then wholly disappear. This major creation of facts on the ground will make the lands, by force, unused and then the request by Palestinians in any negotiations for water for the area will be argued by Israel as baseless.

The Coastal Aquifer, Gaza’s only natural freshwater supply, was at one time providing about 18 percent of Israel’s water. Serious over-pumping from this rather shallow aquifer has allowed salt from the Mediterranean and other nearby saline aquifers to be introduced. Salting, along with pollution from pesticides, fertilizers and fecal matter (the latter mainly from the refugee camps, most of which have no proper sewage control) have rendered this water unfit for drinking in many areas. Citrus, the traditional main crop of Gaza, is highly salt-intolerant and is becoming obsolete. One wonders to what extent the lack of potable water figured in Israel’s decision to pull out of Gaza.

Israel’s Growing Water Shortage and Lebanon

In fact, in spite of controlling the Jordan Basin and the Western Aquifer, Israel is once more running out of water. The Coastal Aquifer is gone and the flow of the Jordan River has dropped 90 percent over the last fifty years, primarily due to over-extraction. Some observers speculate that Israel is once more turning eyes toward the Litani River in Lebanon, the only country in the region with a water surplus.

After the 1967 war, Moshe Dayan, Israel’s defense minister during the war, said that Israel had achieved “provisionally satisfying frontiers, with the exception of those with Lebanon.” Both David Ben-Gurion and Moshe Dayan at various times advocated Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon and the Litani. Over the years, the Litani River has continued to be in Israel’s sights. It’s difficult to know what role water played in Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1978, 1982 and again this year.

During the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon between 1982 and 2000, rumors abounded but were never substantiated that Israel was diverting water from the Litani River. What is known is that Israel prohibited the sinking of new wells, seized all technical documents relating to the Litani and, in the barrage of 1993, drove hundreds of thousands from their homes in southern Lebanon. And in 2006? In a final hard push, the day before the cease-fire went into effect, Israeli ground forces advanced to the banks of the Litani. Again, hundreds of thousands of refugees were driven from their homes.

Israel destroyed vast portions of the water infrastructure of southern Lebanon, including the Litani Dam, the major pumping station on the Wazzani River and the irrigation systems for the farmland along the coastal plains and parts of the Bekaa Valley. As quoted in the LA Times ( 22 August 2006 ), UNICEF water and sanitation specialist Branislav Jekic said, “I have never seen destruction like this…. Wherever we go, we ask people what they need most and the answer is always the same: water. People want to move back to their communities. But whether they stay or not will depend on the availability of water.”

In this issue of Progressive Planning you will read of other struggles for safe, affordable, accessible water in many parts of the world. Many have predicted that wars of this century will be over water rather than oil. Nearly 2.2 billion people, one-third of the world’s population, are thirsting for water. In Haiti, Gambia and Cambodia, people are subsisting on less than six liters of water per day. Millions die every year from water-related diseases. The story of Israel is only one among many of the powerful taking water from those with less power. It is only one among many stories of environmental degradation and wasteful uses of water.

In the United States we only have to look to the High Plains Ogallala aquifer, which runs 1,300 miles from Texas to South Dakota and supplies the breadbasket of this country with its water, to find an even more egregious example of over-pumping: The aquifer is being drawn down eight times faster than nature refills it. And we only have to look to Las Vegas, with its green lawns, swimming pools and golf courses in the middle of a desert, to find a culture even more wasteful of this precious resource. Let us hope that throughout the world, more and more people will look and then act before it is too late.

Marie Kennedy is professor emerita of community planning at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is on the advisory committee and an editor of Progressive Planning and edited this special issue on water.